Operatic Portrayals of Crusade Narratives

Students will trace the history of how crusading ideology was wielded artistically and politically by tracing the portray of crusade narratives on the operatic stage in the early modern period through the 19th century.

This will allow students to understand how the crusades continued to be a source of cultural production throughout Western European history as well as grapple with the ways in which the crusades became a vehicle for both propaganda and political critique.

As an evaluative activity, students will discuss ways in which crusading rhetoric has been deployed by politicians in recent years. They will then break into smaller groups and write a dramatic scene set in the crusades that utilizes this rhetoric and vocabulary. This will allow students to engage in the same kind of process that writers, artists, and composers when attempting to refashion crusading narratives to offer political critique or a laudatory paean.

This will allow students to understand how the crusades continued to be a source of cultural production throughout Western European history as well as grapple with the ways in which the crusades became a vehicle for both propaganda and political critique.

As an evaluative activity, students will discuss ways in which crusading rhetoric has been deployed by politicians in recent years. They will then break into smaller groups and write a dramatic scene set in the crusades that utilizes this rhetoric and vocabulary. This will allow students to engage in the same kind of process that writers, artists, and composers when attempting to refashion crusading narratives to offer political critique or a laudatory paean.

16th Century

1580: Torquato Tasso's La Gerusalemme Liberata

"Erminia tends to Tancredi's wounds" by Alessandro Turchi

"Erminia tends to Tancredi's wounds" by Alessandro Turchi

First published in 1581, Torquato Tasso's Gerusalemme Liberata is a fantastical portrayal of the First Crusade and would go on to become the inspiration for dozens of operas. Composed in the face of conflict between Europe and the Ottoman Empire, the subject matter struck a chord with its Eurpoean audience, and the poem became immensely popular. The story, which revolves around the romantic intrigue of several Christian knights during their pilgrimage to Jersualem, included real historical figures, such as Geoffrey of Bouillon.

Despite Tasso's success, and the immense influence the poem had on both music and fine art, critics were less than thrilled with his mystical and magical characters, and before his death, Tasso heavily revised the poem. This version, however, never gained popularity, and it is the poem in its original form that served as the inspiration for many of the operas listed below.

Despite Tasso's success, and the immense influence the poem had on both music and fine art, critics were less than thrilled with his mystical and magical characters, and before his death, Tasso heavily revised the poem. This version, however, never gained popularity, and it is the poem in its original form that served as the inspiration for many of the operas listed below.

17th Century

1624: Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda by Claudio Monteverdi

|

Composer of the first opera, L'Orfeo, Claudio Monteverdi spent the majority of his early career in the court of Vincenzo Gonzaga I. Monteverdi's patron, The Duke of Mantua, grandson of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, was also closely associated with Torquato Tasso, and in 1624 Il combattimento di Tancredi and Clorinda was first performed. Set for voices and 4 string parts ( a revolutionary moment in the history of orchestration), the story focuses specifically in the combat between Tancredi and Clorinda in Tasso's Geruslamme Liberata. Monteverdi composed this piece in the context of his employer's military expedition to Hungary alongside the Holy Roman Emperor to combat Turks. It represents ways in which the nobility continued to call upon crusader imagery to justify or enhance their military operations, despite their expeditions to be completely unrelated to the capture of the Holy Land. Monteverdi, who actually accompanied Gonzaga to Hungary, would have composed this piece to flatter his patron through his use of chivalric and romantic crusader imagery.

|

1686: Armide by Jean-Baptiste Lully

"La Salle Des Croisades" in the Palace of Versailles

"La Salle Des Croisades" in the Palace of Versailles

The 17th century French royal court saw a resurgence of interest in the crusades. As Louis XIV attempted to gain control of the French nobility, he commissioned a room within the Palace at Versailles dedicated solely to the Crusades (see above). As the nobility sought to ensure that their heraldry would be included in the wall paintings, many created forgeries of charters and vows to prove their ancestral involvement in the crusades. As a result, Louis' determination to purify the French nobility created one of the biggest obstacles in Crusades Studies, as historians now have to contend with a proliferation of 17th century forgeries.

It was in the context that the celebrated composer, Jean-Baptiste Lully (see above)," brought Tasso's Gerusalemme Liberata to the Parisian stage. Considered by many music historians to be his masterwork, Armide was first performed at the Paris Opera in 1686 to great acclaim. The subject matter, chosen by Louis XIV himself, was presented by Lully in a form developed by himself and a frequent collaborator, the dramatist Phillipe Quinalt. The commission of this crusade narrative by the Sun King demonstrates another medium by which he controlled the perceptions and desire of the French nobility to align with his own. The deployment of the crusades as a means by which the aristocracy could validate their ancestry and devotion was a powerful mechanism which enhanced and augmented the vast cultural production of this period.

18th Century

1711: Rinaldo by George Frederic Handel

Emma Matthews (Almirena) performs during a dress rehearsal of Handel's 'Rinaldo' at the Opera House on July 19, 2005 in Sydney

Emma Matthews (Almirena) performs during a dress rehearsal of Handel's 'Rinaldo' at the Opera House on July 19, 2005 in Sydney

German-born composer George Frederic Handel came to London in 1712 after his employer, George the Elector of Hanover came into the English throne as King George I. Handel, who was heavily influenced by the Italian Baroque movement, premiered Rinaldo as the first Italian opera produced for an English theater. The opera was met with great success, and ignited a thirst for Italian opera in the English court. Handel would go on to compose 41 operas over the course of his career.

Rinaldo, based on Tasso's Gerusalemme Liberata, was the most frequently staged opera of Handel's in his lifetime. The crusades narrative, already fully ingrained in the French imaginary was brought to England, which had its own memory and history of wars in the Holy Land. In this sense, the intense of the crusades narrative in England was unprecedented. The origins of tradition of Orientalism in the period, like in France, certainly had an impact on the colonial activities of the English monarchy in the 18th century.

Rinaldo, based on Tasso's Gerusalemme Liberata, was the most frequently staged opera of Handel's in his lifetime. The crusades narrative, already fully ingrained in the French imaginary was brought to England, which had its own memory and history of wars in the Holy Land. In this sense, the intense of the crusades narrative in England was unprecedented. The origins of tradition of Orientalism in the period, like in France, certainly had an impact on the colonial activities of the English monarchy in the 18th century.

1732: Zaire by Voltaire

While Tasso's Gerusalemme Liberata dominated as the literary source for crusades operas in the 17th century, in 1732 Voltaire published a play set in the crusades titled, Zaire. This play found immense success internationally, and was praised by critics, who had often pointed to Volatire's failure to include romantic plots in his dramas.

While at first glance the play reads as a sentimental romance, Voltaire's conflation of militant faith and romantic love proffers a scathign critique of religion that is typical of the Enlightenment. He himself cited the crusades as, "follies that cost two million lives," and the crusading context for this tragic play allowed him to subtly critique the crusades in a time where European colonialism had begun to take shape.

It also proved to be a hugely popular libretto for operas, with 13 operas using the text as a literary source throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

While at first glance the play reads as a sentimental romance, Voltaire's conflation of militant faith and romantic love proffers a scathign critique of religion that is typical of the Enlightenment. He himself cited the crusades as, "follies that cost two million lives," and the crusading context for this tragic play allowed him to subtly critique the crusades in a time where European colonialism had begun to take shape.

It also proved to be a hugely popular libretto for operas, with 13 operas using the text as a literary source throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

19th Century

1824: Il Crociato in Egitto by Giacomo Meyerbeer

|

The 19th century brought with it new crusader narratives to the stage. In addition to the Tasso and Voltaire texts, new literary sources were introduced to the stage. In 1824, Giacomo Meyerbeer, one of the most prolific and most popular composers of the 19th century, became an international sensation with his crusader opera Il crociato in Egitto. An early example of grand opera and the last opera to have a castrato part, Meyerbeer set his opera in the Sixth Crusade in Damietta. The plot follows a Christian knight who becomes the confidante of the Sultan in Egypt, falls in love with his daughter, and secretly converts her to Christianity. After being imprisoned by the Sultan, he goes on to dave him from a treacherous plot. The Sultan then relents and releases him from prison.

Napoleon's ultimately unsuccessful invasion of Egypt and Syria in the early 19th century had sparked a wave of Orientalism in France, and the memory of the crusades was certainly a part of the revived interest in the Near East the persisted throughout the 19th century, particularly in French and Britain. Meyerbeer was only one of many 19th century composers to present their operas in "exotic" places and times. |

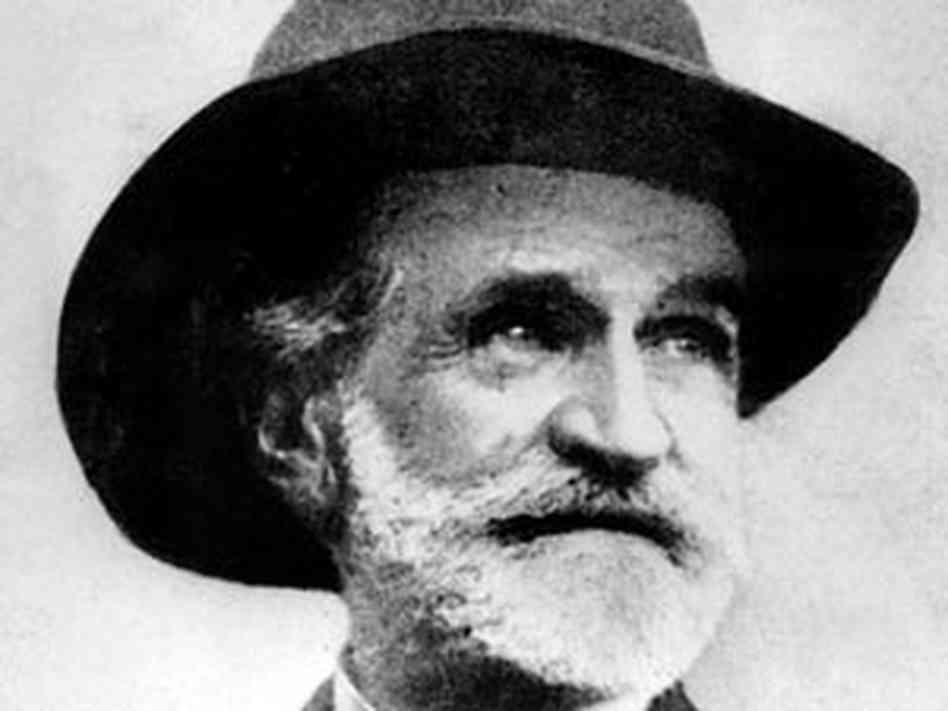

1843: I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata by Giuseppe Verdi

|

Later rewritten for the Paris Opera as Jerusalem, Giueseppe composed I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata using a epic poem written by Tommaso Grossi as its source text. The opera follows a Milanese contingent on the First Crusade. It is undoubtedly politicized by the context of the Risorgimento, of which Verdi was an avid supporter. In fact, I Lombardi came under the scrutiny of the police in Austrian-held Milan, who saw the portrayal of Italians united against a common enemy as incredibly dangerous.

The narrative takes place mostly in Milan, Antioch, and outside Jerusalem. Like so many of the other crusader libretti, it involves a romance between Christians and non-Christians, political intrigue, and betrayal. It is not, however, a panegyric to the history of the Crusades or a a portrayal of the desire for conquest, but a critique of violence and conquest. In critiquing the ambitions and cruelty of the crusaders, Verdi was able to simultaneously critique the occupation of his own country and offer a paean for peace and unity. |