The Influence of French Gothic Architecture in the East

The purpose of this exercise is to teach students the basic elements of French Gothic architecture in order for them to be able to recognize these elements in crusader architecture of the East. Being able to recognize Western artistic elements in Eastern structures will allow students to better understand the socio-political aims of a given building program. For example, if an Eastern Orthodox church was altered by Frankish crusaders and made to look like a Western Gothic structure, it could be possible that the crusaders were attempting to demonstrate the superiority of Latin Christianity and its building practices. If Frankish crusaders began building a structure in the Western Gothic style, but with certain Eastern elements, they could be attempting to legitimize their place in the East by incorporating themselves into the Eastern artistic tradition and claiming to be a part its history. A base knowledge of the Western Gothic style and its building phases will allow students to discern the socio-political aims of crusader architecture in the East.

The Phases of French Gothic

Early Gothic 1140-1200

High Gothic 1200-1240

Rayonnant 1240-1350

Late Gothic or Flamboyant style 1350-c. 1500

High Gothic 1200-1240

Rayonnant 1240-1350

Late Gothic or Flamboyant style 1350-c. 1500

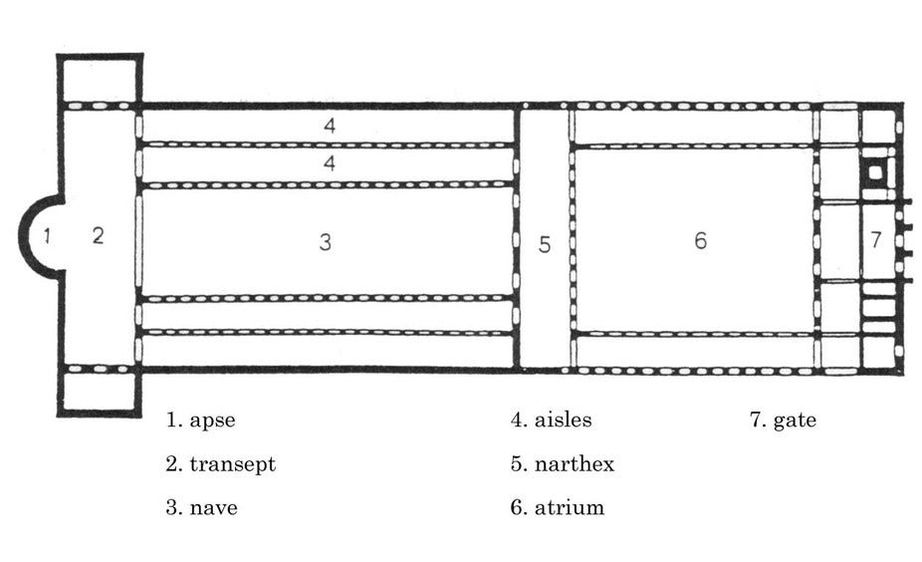

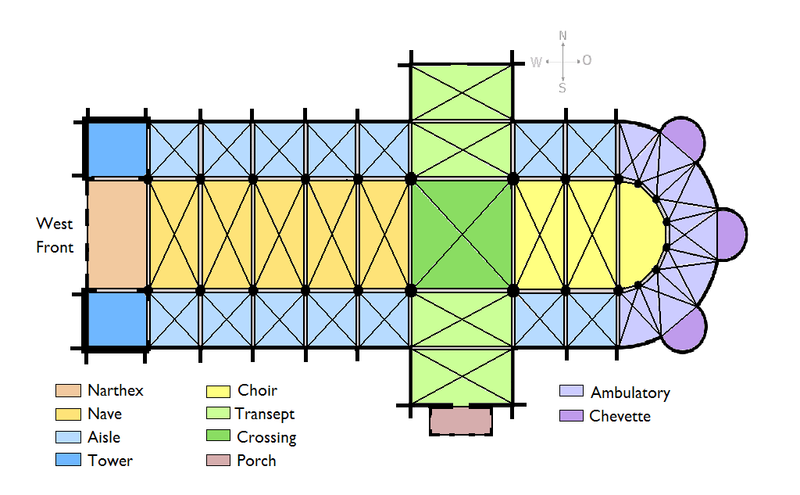

Ground Plans

The transition from Romanesque basilica style ground plans to Gothic ground plans, was marked by the addition of a choir, ambulatory, and chapels in the east end, the extension and enlargement of the transepts, and the elongation of the nave and side aisles.

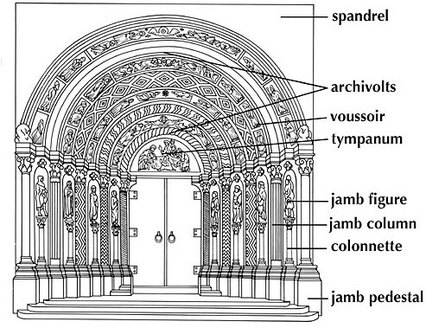

Portals

|

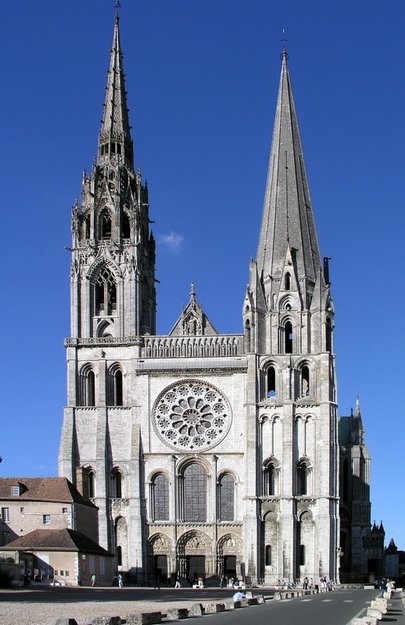

As the phases of Gothic architecture progressed, portals became enlarged, more ornate, and more detailed. The tympanums began to contain elaborate narrative scenes, often of the Last Judgement, the Death of the Virgin, or the Annunciation. High and Late Gothic portals contained a rose window, like that of Reims Cathedral, which served to further dematerialize the exterior of the structure. During the evolution of the Gothic style, archivolts began to contain extremely detailed sculptural decoration and the jamb columns were also ornamented with biblical figures and saints, known as jamb figures.

|

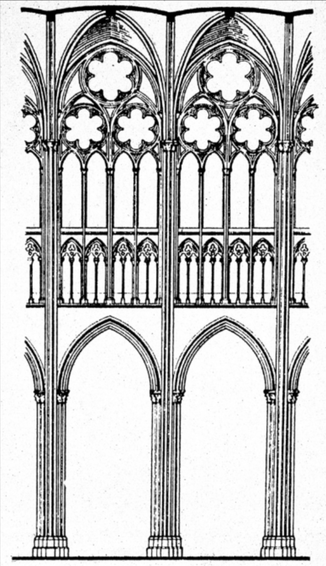

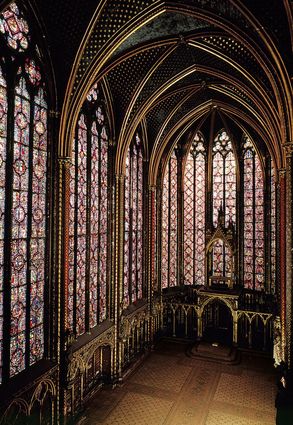

Naves

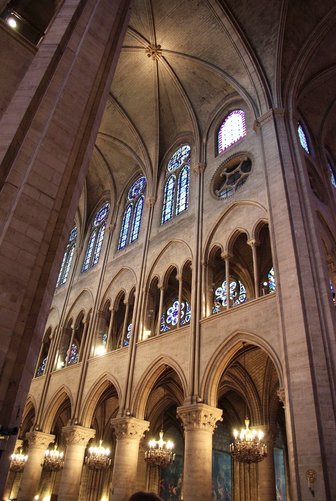

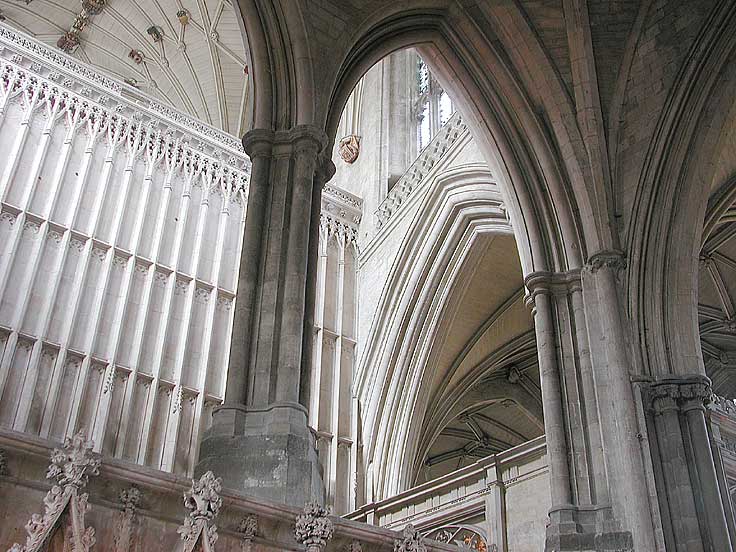

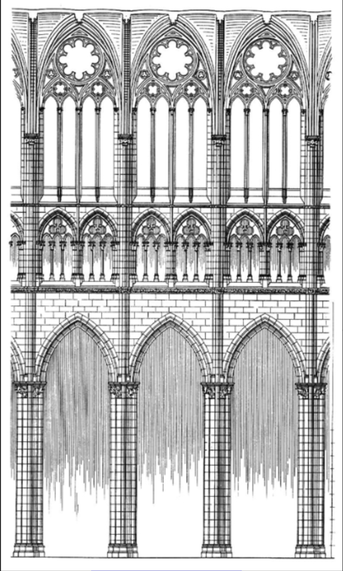

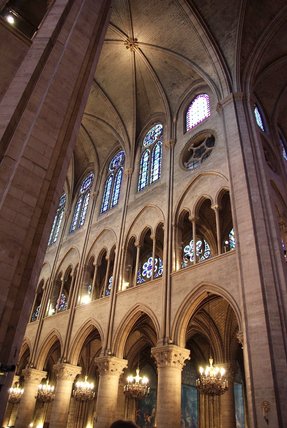

During the transition from Romanesque to Early Gothic, and then on into the Later Gothic, the walls of the nave began to dematerialize, and stained glass began to take up a more prominent space in the construction of the nave. The skeleton like naves of the later Gothic required a new architectural innovation: external buttressing. External buttressing is found in Gothic structures, and served to support the very thin walls of the nave. A great example of the dematerialization of the nave appears in the nave of Notre-Dame in Paris. The cathedral's nave went through several building phases, which make the gradual dematerialization of the wall visible.

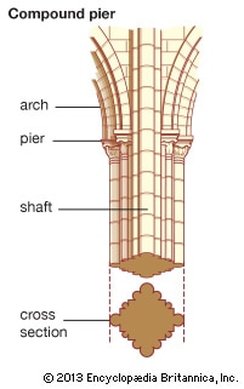

Naves continued to dematerialize into the Rayonnant period. The columns of the nave of Notre-Dame (as seen above) eventually fell out of use and were replaced by compound piers that flattened and thinned the appearance of the walls. The triforium and clerestory windows began to take up more space in the walls of the nave, which served to dematerialize the walls.

Students should then take the following quiz, which contains images from a variety of French Gothic cathedrals in France. The aim of the quiz is for students to be able to roughly date the buildings by discerning which phase of Gothic architecture each building is a part of.

| flash_cards.pdf |

Frankish Architecture in the East

Frankish ecclesiastical architecture in the Crusader States is similar to that of the West with some discrepancies as a result of factors such as available building material, laborers, and time. The Latin Christian churches of the crusader states were often more simple in construction and ornamentation than the Rayonnant and Late Gothic cathedrals of the West, as their builders were usually pressed for time or building in a hostile frontier environment.

Saint Nichols in Famagusta

Northern Cyprus

Saint Nicholas in Famagusta was a Frankish cathedral located in the Latin Kingdom of Cyprus. Cyprus was first conquered by Richard the Lionheart in the 12th century. Work on the Saint Nicholas began in 1300 and continued on for the following decades. The church served as the coronation site of the Lusignan kings of Jerusalem.

Questions for Students

- According to the date, what phase of architecture was occurring in France at this time?

The construction of the church began in 1300, which would have been the Rayonnant phase in France - What phase does the Saint Nicholas fall into based on the images of the nave? What architectural features led you to this conclusion?

The nave contains pointed arches, quadripartite vaulting, and a large clerestory window, but no triforium or stained glass. Additionally, columns line the nave, a feature which resembles the Early Gothic construction of Notre-Dame's nave, which also contains columns rather than piers. The interior of Saint Nicholas more closely resembles an Early Gothic structure than a Rayonnant one.

- What phase does the facade fall into based on the images? What architectural features led you to this conclusion?

The central typanum contains a rose window, a feature typical of the Rayonnant phase and similar to the facade of Reims Cathedral. The three portals all contain high pointed gables and elaborate tracery, features typical of the High Gothic and Rayonnant styles. - What do you think caused these architectural discrepancies?

It is important to consider that the crusaders who were responsible for building Saint Nicholas may not have been exposed to the High Gothic style of the West at the time they were building, as they may have departed for the Holy Land when the Early Gothic was still the primary style and thus built the nave in the style familiar to them. Given that building continued on Saint Nicholas in the decades following 1300, it is possible that the façade was a later addition done by someone who was familiar with the High Gothic and Rayonnant styles.

Our Lady of Tortosa

Northern Tripoli

Our Lady of Totosa, located on the Northern coast of Tripoli, was begun in the second quarter of the twelfth century and completed in the thirteenth century. The town of Tartous, where the church is located, was originally founded in antiquity but rebuilt by Emperor Constantine I in 346 CE. Tartous was an active city in the Byzantine era thereafter, until it was occupied by crusaders in the 12th century.

Questions for Students

- The church follows a basilica style plan and contains both Gothic and Romanesque architectural elements. What Gothic elements can be observed in the images of the interior and exterior of the church?

The main center door has the very basic elements of a portal and tympanum. Although there is no ornamentation and no high pointed gables above it, the tympanum is slightly pointed, there is a receding jamb, and archivolts around the central door. Although not highly ornamented as they would be in the West, these elements are the foundational architectural elements of the Western Gothic portal. On the interior of the church the ceiling is comprised of barrel vaulting, which is a Romanesque feature. However, the vaults extend downward into compound piers, a feature also typical of the Gothic style.

Sources For Students

The following are sources that can be used for the study of both Gothic architecture in the West and Crusader architecture in the East.

Boas, Adrian J. Crusader Archeology: Material Culture of the Latin East. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2017.

Bony, Jean. French Gothic Architecture of the 12th and 13th Centuries. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Folda, Jaroslav. Crusader Art: The Art of the Crusaders in the Holy Land, 1099-1291. Hampshire: Lund Humphries, 2008.

Folda, Jaroslav. Crusader Art in the Holy Land: from the Third Crusader to the Fall of Acre, 1187-1291. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Francis, R.B. The Medieval Churches of Cyprus. London: Ecclesiological Society, 1949.

Wilson, Christopher. The Gothic Cathedral: The Architecture of the Great Church, 1130-1530. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1990.

Boas, Adrian J. Crusader Archeology: Material Culture of the Latin East. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2017.

Bony, Jean. French Gothic Architecture of the 12th and 13th Centuries. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Folda, Jaroslav. Crusader Art: The Art of the Crusaders in the Holy Land, 1099-1291. Hampshire: Lund Humphries, 2008.

Folda, Jaroslav. Crusader Art in the Holy Land: from the Third Crusader to the Fall of Acre, 1187-1291. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Francis, R.B. The Medieval Churches of Cyprus. London: Ecclesiological Society, 1949.

Wilson, Christopher. The Gothic Cathedral: The Architecture of the Great Church, 1130-1530. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1990.